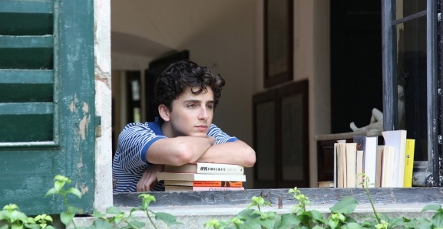

CALL ME BY YOUR NAME

Cast: Timothee Chalamet, Arnie Hammer, Esther Garrel, Michael Stuhlbarg, Amira Casar

Director: Luca Guadagnino

130 mins

Elio (Timothée Chalamet), is an American teenager who is spending a sweltering summer break with his parents in Northern Italy. He has made fixed plans at midnight to meet Oliver (Armie Hammer), the graduate student billeting in the guest bedroom next to his. The two have already kissed secretly in the grass by the side of a dirt road; they would seem to be on the way to becoming lovers. Elio goes about his day as normal, taking meals with his family, playing the piano in the main room, and even having sex with his girlfriend, all seemingly spontaneously, and yet in actuality set to the rhythm of his own personal, internalised countdown towards a midnight tryst with Oliver.

There is a pronounced show of restraint within a lyrical conception that is quietly impressive about Call Me by Your Name. The film doesn’t overstep itself in any way, and in adapting André Aciman’s 2007 novel, Guadagnino and screenwriter James Ivory have produced a film that simultaneously analyses and dramatises issues of sexuality, religious identity and privilege—with much well-read bourgeois lazing about in the sun and yet without straining against its clearly marked narrative boundaries as a coming-of-age romance, or exploding its form as an accessible, fundamentally pleasing upper-middlebrow entertainment. It takes a tremendous amount of skill and intelligence to produce a film that possesses potentially broad appeal without sacrificing complexity or a serious tone.

If there’s a potential weak spot here, it’s Hammer. Not his acting, which is as precise and as charming as it needs to be, but his casting as a 24-year-old Jew, (he’s 31 at the time of writing), considerably strains credibility on both fronts. Despite this, Hammer is very good, and because of Oliver’s slightly implausible physical and intellectual superiority, and the ways that it’s humorously and then touchingly undermined by his attraction to Elio, it is necessary to give Call Me by Your Name its humid air of desire, as well as the slightly enchanted feeling its ancient setting demands. Elio and Oliver’s fast friendship does not set off any immediate alarm bells within the small, conservative town, because it looks basically identical to all the other hearty homo-social bonding going on in the bars and bike paths. Their extended, intricate flirtation passes unnoticed even as it’s out in the open. A fine performance too from Michael Stuhlbarg eight years after his breakthrough in A Serious Man. With the slightly halting, and yet completely compassionate and open-hearted, content of his speech to his son, which encompasses tones of pride, empathy, encouragement, commiseration, and, just as delicately and perceptibly as Ivory’s script intends, a curious sense of regret over roads untaken, provides a rare example of a film clearly articulating its themes without overstating them.

Cast: Andrew Garfield, Claire Foy, Hugh Bonneville, Tom Hollander

Director: Andy Serkis

117 mins

A prestige biopic may at first seem like an odd task for motion-capture

expert Andy Serkis to take on in his first stab at directing, but Breathe is in

some ways not all that different from his previous films with which he's been

involved as an actor. Not long after the words “What follows is true” flash on

the screen in the opening shot, that truth is revealed to be a clean, easily

digestible replica bathed in honeyed cinematography and sentimentalised

adulation. This isn't to suggest that Serkis's approach to the biopic

is neither particularly unique in glorifying its subject for the sake of

inspiration nor that his intentions are in the wrong place. In fact, his

portrait of Robin Cavendish (Andrew Garfield), a man paralysed in 1958 from the

neck down by polio and forced to breathe with the assistance of a respirator,

is at times quite moving. But the filmmaker's intensely personal connection to

his subject matter is evident in Breathe's perpetual aggrandising of Robin

(Serkis has had a longtime friendship with Robin's son, Jonathan, who also

produced the film). As such, it doesn't come as a surprise that triumphant

moments of overcoming hardships are thrust to the forefront as years of mental,

emotional, and physical hardships are barely touched upon.

Breathe is most effective when it engages with the world beyond the self-contained love story between Robin and Diana (Claire Foy) to examine the former's pioneering work as a disability advocate. But despite its title, the film is often suffocated by its limited scope and refusal to delve into Robin and Diana's tortured interior worlds. Even after Robin learns that he's paralysed and likely has months to live, Serkis allows only a few brief scenes of the man struggling to learn to swallow, talk, and overcome his suicidal depression. And soon, the film abruptly switches gears into a lighthearted romp as Diana helps Robin escape the hospital to live under her care at home. Such levity is relied on so often throughout the film that it becomes a crutch, preventing an honest engagement with the myriad difficulties faced by Robin. And he certainly faces a steady stream of challenges even following his initial paralysis—from implementing his idea for building a respirator into a wheel with the help of his close friend, professor and inventor Teddy Hall (Hugh Bonneville), to building a hydraulic lift into the front seat of a car and later finding funding to mass produce his revolutionary wheelchairs. But as difficult as Robin's life is, victory here comes without breaking a sweat and major hurdles are cleared with the ease of a seasoned track and field athlete.

The effortlessness with which Robin and Diana move through their years together is particularly egregious when they travel to Spain, trying to keep their previously adventurous lifestyle comparatively alive. When Robin's respirator packs up, a passer-by quickly helps them contact Teddy, so that their friend can fly out and rescue them. As Robin and Diana wait, various townspeople visit them by the roadside, and what follows is a full-out party celebrating the miracle of Robin's survival despite his condition. Along with polio, Breathe would have you believe Robin caught the magic touch as well.

This spell of unending optimism is finally broken toward the end of the film, when Robin travels to Germany to see the unconscionable manner in which renowned doctors care for their disabled patients and is subsequently moved to free them from their inhumane conditions. His speech to a room full of doctors and nurses is heartfelt despite its cloying sentimentality, but it's the unexpected grace of the ending that finally allows for a true sense of self-reflection and emotional purging that much of the film mutes. Despite hitting most of the predictable biopic beats along the way, Breathe ends with an extended, meditative sequence that doubles as an impassioned plea for the humane treatment of the disabled and the right to death with dignity.